The economic effects of automation aren't what you think they are

This post is the new FAQ article on automation for the reddit r/economics forum.

One trend in the last decade has been increasing fears of AI and other machines automating away jobs. Whether it’s Elon Musk, a US presidential candidates, or a famous youtuber there’s serious concern that job automation could cause long run unemployment at massive scales.

Job automation underpins the explosion of economic growth we’ve seen since the 1830’s industrial revolution. It’s almost impossible to study any economic trend it creates in isolation, because the entire labor market has been tied to job automation for 200 years. Be skeptical of any simplified “grand unified theory” of automation’s effect on unemployment.

This FAQ will separate job automation facts from myths. There are large scale problems on the horizon, but they may not be what you think they are. It will also discuss some solutions which could improve the future labor market.

The Facts

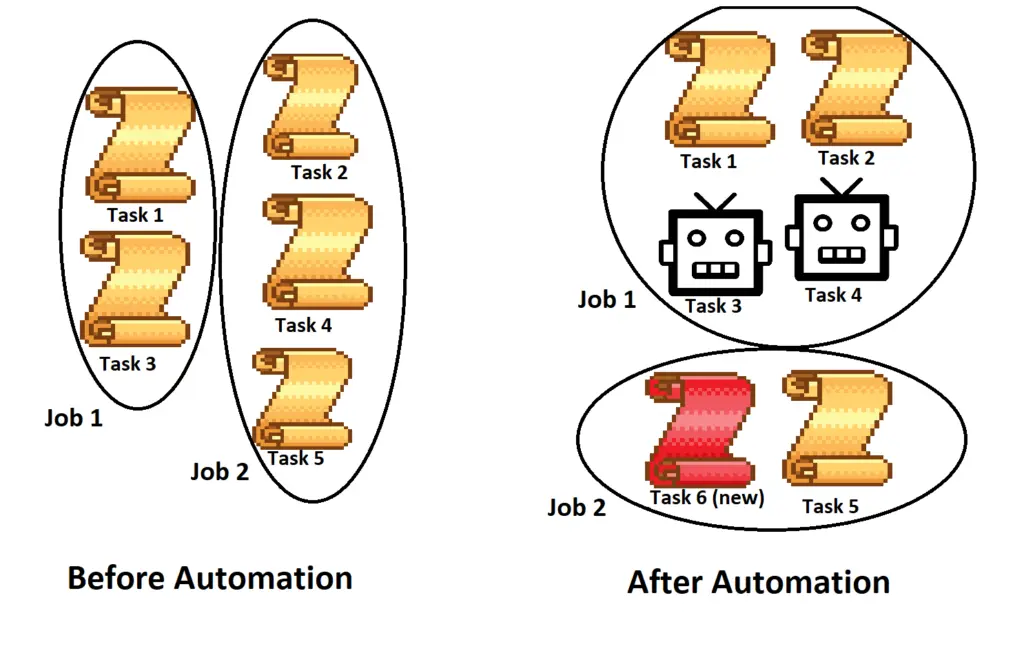

1) We automate tasks, not jobs

A job is made from of a bundle of tasks. For example, O*NET defines the job of post-secondary architecture teacher as including 21 tasks like advising students, preparing course materials and conducting original research.

Technology automates tasks, not jobs. Automating a task within a job doesn’t necessarily mean the job will stop existing. It’s hard to predict the effects – the number of workers employed and the wage of those workers can go up or down depending on various economic factors as we’ll see later on.

When you read an alarmist headline like “Study finds nearly half of jobs are vulnerable to automation”, you need to put it in context: nearly half of all jobs contain tasks ripe for automation. Those jobs may or may not be at risk.

For example, some of an architecture professor’s tasks are easier to automate (grading assignments) and others are harder (advising students). According to Brynjolfsson and Mitchell tasks “ripe for automation” are tasks where:

-

The task provides clear feedback with clearly definable goals and metrics

-

No specialized dexterity, physical skills, or mobility is required

-

Large digital datasets can be created containing input-output pairs for the task

-

No long chains of logic or reasoning that depend on diverse background knowledge or common sense

Some task are inherently hard automate. Moravec’s paradox says that it’s easier for a computer to learn to beat the best humans at chess or Starcraft than it is to do basic gardening on a windy afternoon. This is true even though almost all humans can do basic gardening and only a few can play chess at the highest levels.

The paradox is explained when we understand that gardening requires learning sensorimotor skills that mammals have evolved over billions of years, whereas learning Chess only means learning a short ruleset some humans developed when they were bored. This is true whether we’re programming the computer manually or using the latest deep learning methods.

Some other tasks don’t require dexterity, but require the sort of cross-task general intelligence that we simply can’t encode into a machine process (with or without machine learning). “Conducting Original Research” is a good example of this.

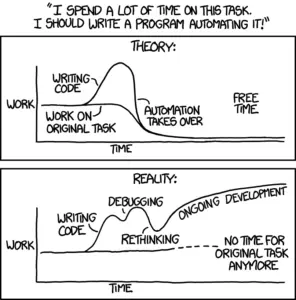

Lastly, some tasks are simply bad candidates for automation because they’re not very repetitive or too context driven for automation to be economic, as shown in this XKCD comic:

2) Humans are not horses

YouTuber CGP Grey’s Humans Need Not Apply makes a famous argument: humans today are in the same position horses were in the 1910s. He says that humans will soon be entirely redundant and replaced by machines which can do everything a human can, but more efficiently.

This argument is wrong and uninformed.

Horses have only ever served very few economic tasks: transporting heavy loads, transporting humans faster than foot travel, and recreational uses. With the invention of the combustion engine, two of those three tasks are automated, and horses became almost exclusively a recreational object. This means horses populations decreased over time, because they were no longer needed for labor (the human equivalent to the horse depopulation would be mass, long term unemployment).

Humans can do lots of tasks (O*NET lists around 20,000). Even though most jobs contain some tasks that can be automated, most tasks themselves are not suitable for automation, whether it’s with machine learning or any other method.

It’s also important to realize that automating a task means broader economic changes. It can change what jobs exist, by redefining which tasks are worth bundling together. It will also create entirely new tasks (eg. managing the new automated processes).

Automating a task does not mean there is “one fewer” task to be done in the economy. This line of thinking is called the lump of labor fallacy. Any argument whose logic assumes there’s a finite amount of work in the economy is fallacious and wrong.

The industrial revolution itself shows why the lump of labor fallacy is wrong.

Before the invention of the steam engine, more than 95% of humans were employed on farms, whereas today this number is around 2%. The remaining 93% of the population didn’t disappear or go out of a job. Instead, automating farm work freed up the labor force to be put to more productive use over time. Some young laborers went to school instead of working on the family farm, while others started working in factories. Over time, the labor force reallocated away from agriculture and into manufacturing and services.

Similarly, as tasks are automated in the modern economy (such as manufacturing tasks) workers will shift their time into other tasks like the growing service economy

3) Automation can help or hurt depending on who you are

Automation does not impact everyone equally. If technology automates some important task in your job, the effect will differ depending on relevant economic factors: what job you do, where you are geographically, what your education level is, your level of wealth, and your social/professional network.

It’s almost impossible to know a priori what the outcome will be. Let’s take the example of a radiologist, where a core task of the job (making diagnoses based on X-Ray images) could be automated in the future. The scenario where all radiologists are unemployed overnight is unlikely – they have at least 28 other tasks to work on that still need doing. That said, several scenarios can play out:

-

Because their workload is more automated, radiology becomes faster and more convenient. More doctors request radiology services, and more patients use radiology services. More medical students enter radiology, or existing radiologists make more money.

-

People don’t want/need more radiology services. Because a radiologist’s workload is reduced, there are fewer radiologists. Existing radiologists become unemployed while looking for new specialties

-

People don’t want/need more radiology services. Existing radiologists can’t/don’t find new specialties. We have as many radiologists, but they’re paid less.

As we see, in the same case, our radiologist can end up making more money, less money and keep his job, or lose his job entirely. Which scenario plays out depends on economic factors like the elasticity of supply/demand, the substitution effect, the income effect.

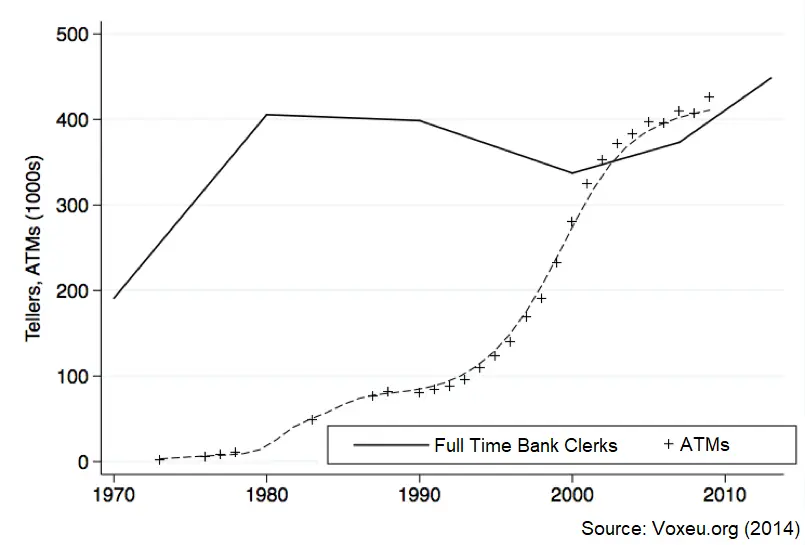

Second example: When ATMs were introduced to banks in the 1980s, people thought bank tellers would quickly stop existing. Over time, each bank branch did end up employing fewer tellers. However, ATMs made it cheaper to operate bank branches, so more bank branches opened and there were eventually more bank teller jobs over all:

A final example of automation leading to unexpected job growth is the invention of spreadsheet software. In 1985 there were two million bookkeepers in the United States. Today there are only about one million. Between those two dates, spreadsheet software revolutionized a bookkeeper’s daily work.

However, while the number of bookkeepers halved, the number of accountants and auditors doubled (roughly 1.8 million jobs) and the number of financial analysts exploded (around 2.1 million jobs). Of the million people who stopped working as bookkeepers, many were freed from the most boring tasks in their job and were able to move into more interesting, productive work rather than being discarded.

This shows that it’s extremely difficult to predict the effect of automating a task on the workers who do that task.

4) Automation may be linked to rising inequality

Automating work makes a country richer on average in the long run. This doesn’t mean that everyone will get richer – automation can increase or decrease economic inequality.

A quick example - a task gets automated and a common good is now much cheaper to produce. This could translate into lower prices, leading to widespread consumer gains and lower inequality. But it could also lead to equivalent prices and higher profit margins, which would increase inequality. Which scenario happens depends on market concentration, among several factors.

Inequality in the USA has increased in the last 30 years. There is some evidence that this is partly the result of recent technological progress, AKA automation.

This seems to be at least partially due to technology. Automation is mostly attacking tasks in what we would call “middle skill” jobs.

This fact makes sense with what we learned about Moravec’s paradox in section 1. Lower income jobs are often manual and dexterous, and Moravec’s Paradox means they are protected from being efficiently automated. On the high end of the scale, managerial and highly specialized tasks in jobs are of the kind that is often very domain driven and non-repetitive that makes them uneconomical to automate. Overall, high amounts of middle-skill job automation would lead towards a polarized workforce with more jobs at the high-end and low-end, fewer jobs in the middle and increasing inequality.

It’s not clear if the worsening income inequality is entirely because of technological change. There are several trends that might push down the wages of regular workers compared to high income workers:

-

Firms may have increasing monopsony power over low wage workers. Because there are fewer firms, workers are in a worse bargaining position. This means lower wages overall than in a more competitive marketplace.

-

In most large cities, the cost of housing is outpacing the rate of wage growth. While a worker could have the same pay, the inequality between owners and non-owners will increase, and the share of income dedicated to housing will increasing (leaving disposable income lower).

-

In the US, healthcare prices far outpaces wage growth. This means higher health insurance premiums. While many workers’ total compensation is increasing, their take-home pay is not increasing at the same rate due to the growing share going to health insurance.

-

As we’ll see in section 7, internaitonal trade changes worker-employer dynamics much like automation does. While free trade is good for the population as a whole, some subgroups are left worse off.

5) Automation’s effect on your income seems to depend on education

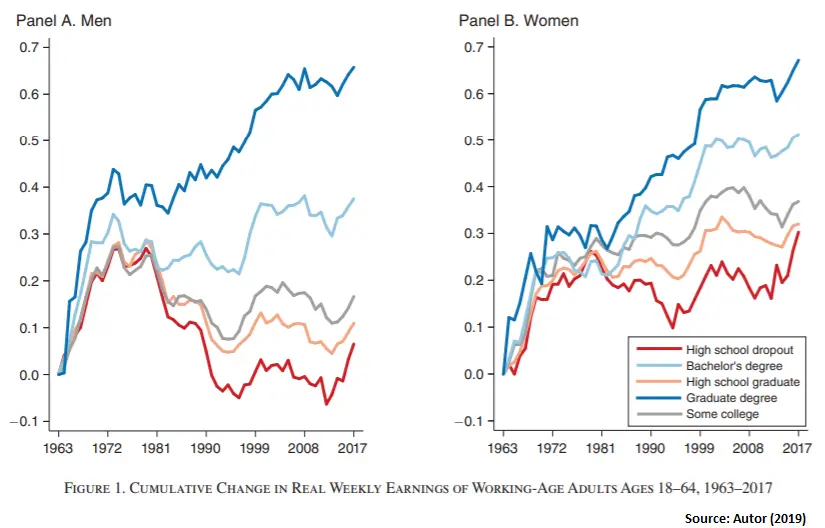

The inequality between workers with different education levels is increasing:

In this chart, the X axis is time, and the Y axis represents the overall percentage increase in wages since 1963. This data shows that while males with Masters’ and Doctorate degrees have gotten a 70% raise in income, male high school dropout haven’t increased their wages compared to 1963.

New technology does not impact all workers in the same way. New technology may make high-skill workers far more productive while not impacting the productivity of low-skill workers. This idea is called Skill-Biased Technological Change (SBTC), and argues that even if automation is not causing job loss, it could still increase inequality by making only high wage workers become more productive. 85% of Economists believe SBTC to be a leading explanation for increasing income inequality.

If a nation’s job market is increasingly polarized between high and low end jobs - and if technological change is also making high-skill workers disproportionately more productive - this type of increasing gap between high education and low education workers could be the result.

The gap between earnings of college graduates and non-college graduates is called the college-wage premium, and it has been increasing for decades.

While the income of college graduates is increasing, this doesn’t mean the lifetime disposable income increases at the same rate. Colleges are in a position where the value of their product sold (the college degree) is increasing sharply. This leads colleges, especially in the US, to be in a position to extract economic value from the college wage premium by increasing their prices [footnote] College degrees increase wages by 3 mechanisms: increasing hard knowledge, improving your social network and the market signal a college degree sends.

It’s hard to argue that the dramatic increase in the cost of tuition can be matched to an equivalent improvement in school curricula (standardized test scores haven’t improved much over time) or in professional networking.

So the college wage premium is likely because the value of the market signal a college degree sends has increased dramatically. Going back to Spence (1973)'s Nobel winning paper on signalling, we know the cost burden of this signal will fall on those emitting the signal, AKA the students. [/footnote]

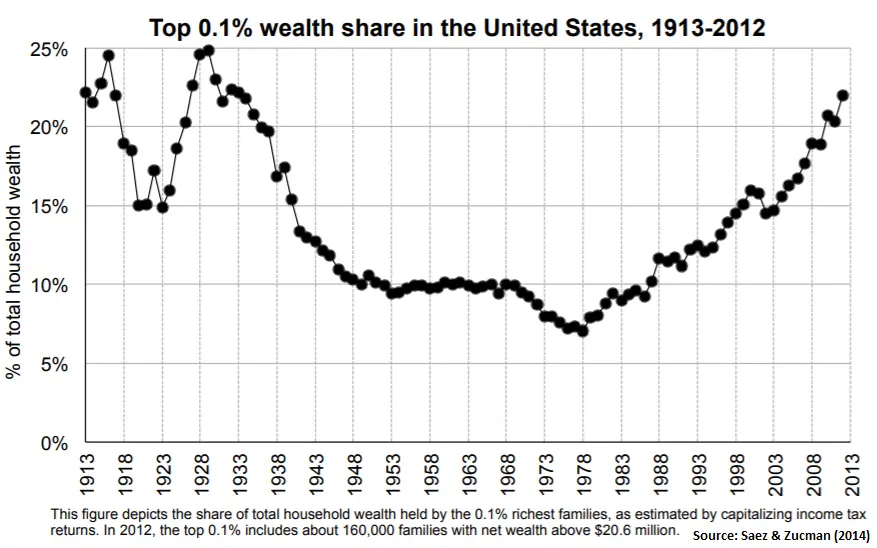

6) Automation might be increasing wealth inequality

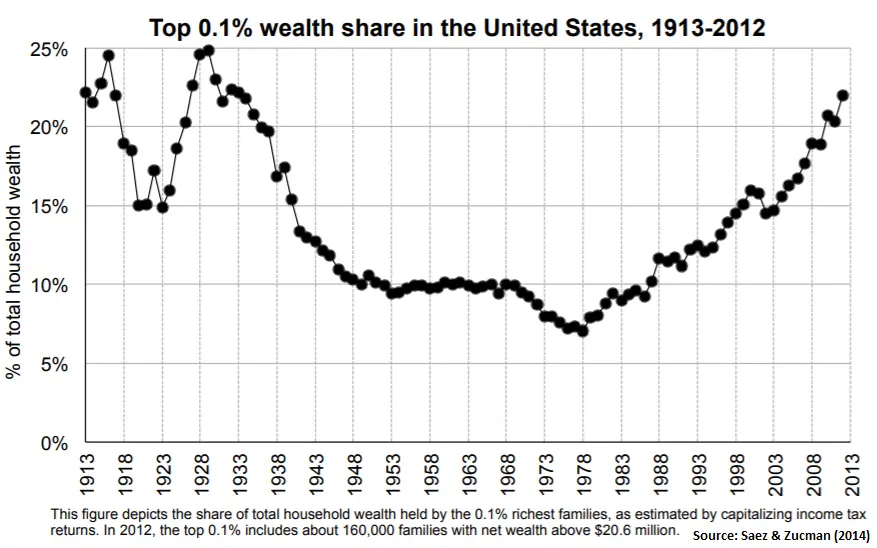

While income inequality has increased significantly, wealth inequality has increased even more since 1980:

If a product or service is made cheaper by automation, the economic gains can go to consumers (lower prices) to workers (higher wages) or to the owners of the firm (higher profit margins). Much like with jobs in section 3, which happens is impossible to predict a priori.

However, wealth inequality is increasing, and automation could be contributing. One way is through deepening automation, where an already automated task is made even more productive. Automation could also displace labor more than it enhances productivity, which would siphon the economic benefits away from workers over time.

7) Automation and free trade have similar effects on labor

This is a sidenote, but will help organize your thoughts on economic trends.

In both the cases of free trade and automation, we replace what was previously done by labor with capital. For trade, we do it by giving the money to people in an other country in exchange for the task being completed. For automation, we do it by giving money to people to make machines to complete the task.

There is a reasonable argument that trade has had a much larger impact on employment in the US in the last 20 years. The reason for this is that trade with China has had a large effect on US manufacturing employment, much more so than automation.

Both trade and automation are fundamental drivers of modern economic growth. Both create more wealth, but also change the distribution of income in society, which often increase inequality. Even the simplest trade models predict that inequality increases – trade creates winners and losers, but winners always gain more than losers lose.

Autor, Dorn & Hansen (2016) put it best:

In response to a given trade shock, a lower-wage employee experiences larger proportionate reductions in annual and lifetime earnings, a diminished ability to exit a job before an adverse shock hits, and a greater likelihood of exiting the labor market, relative to her higher-wage coworker.

In theory, we could compensate the ones losing from trade or automation by taxing the winners’ increased wealth, but in practice this generally seems lost in the political process

8) Solutions

Andrew Yang’s 2020 presidential campaign frequently highlighted the perceived dangers of automation. Because of Yang’s efforts, one of the most common policy solutions linked to automation is a Universal Basic Income (UBI). Yang says that a UBI will act as a safety net against technological unemployment.

UBI isn’t necessarily a bad idea [footnote] UBI can be made mathematically equivalent to most welfare system with taxes coming in and welfare checks coming out. The advantages of UBI are that it’s simpler to understand and might be lighter on bureaucracy. The important part is how much we tax and give out at each level of income. In UBI, we give everyone money unconditionally. If we want to help the poor, then comparing to other systems we need to tax less at lower income brackets, and tax more at higher inome brackets, so that the “gift” is offset by higher taxes. [/footnote] on its own merits. But we saw before that the problem with automation isn’t technological unemployment, it’s low quality job prospects from a shifting economy.

UBI, like any other generous social safety net, helps those out of a job. It can help redistribute after-tax income, but it’s not all that different from simply enhancing the existing welfare state. And it doesn’t specifically address the root cause (education levels and job transitions) so it’s not helping with the long term negative trends we discussed.

Furman (2016) proposes the following solutions:

-

Keep investing in AI/automation technologies because the benefits massively outweigh the negatives.

-

Ensure more widely accessible and flexible education for all to prepare for jobs of the future

-

Put more serious effort to aid workers in job transitions

-

Ensure that the benefits of automation are broadly shared through the welfare state

Furman’s proposals attempt to keep the massive gains from automation, while still addressing the core issues that increase inequality.

TAKEAWAYS:

Don’t be concerned about hypothetical future unemployment.

Instead, be concerned about low quality job prospects right now.

Automation and technological change are fundamental drivers of economic prosperity. However, this prosperity is not necessarily shared equally. When we automate tasks, it’s possible some people will be worse off afterwards.

In the last 30 years there’s a strong case that automation has increased inequality. While we shouldn’t be concerned about wide-scale net job loss or humans becoming economically useless, we should be concerned about stagnating wages, inequality, and large demographics feeling useless due to dire job prospects.

The two groups that are doing well are the highly educated and owners of capital. Both of these groups, but especially the ultra-rich who own a great deal of capital, have had great run of increasing income.

Middle-skill and low-education workers have been negatively impacted the most. It’s not a coincidence that rural inhabitants with low education is one of the only demographics in the last century whose life expectancy has worsened. This increase in mortality is mostly due to “deaths of despair” (suicide, drug overdose, etc).

In short, don’t worry about the imaginary future issues automation might cause when there are very real economic issues automation right now. Let’s focus on those.