Why You Should Not Hire a Real Estate Agent

Today I’ll show why it is a big mistake to hire a real estate agent if you are selling your house (in the current market).

In common practice, the real estate agent takes a percentage cut from the sales price. In exchange they help you sell your house.

People intuitively think that the seller will pay the agent’s fees, through a higher price. For instance, if you planned to sell your $100k you might sell it for $106k to cover the agent’s 6% fees.

Is this really the case?[footnote]Spoiler: no[/footnote] First, we need a detour through the economics of cost incidence.

Cost Incidence

We’ve known for a long time that the financial burden of a cost rarely falls where you think it will.

For example, if the government implements a tax on corporations, the incidence might fall on the employees, customers or shareholders[footnote]Not the corporation. Despite what people will tell you, the corporation isn’t a person. A person will end up paying the tax[/footnote]. Who ends up paying it is generally the result of the web of bargaining power relationships between each economic agent.

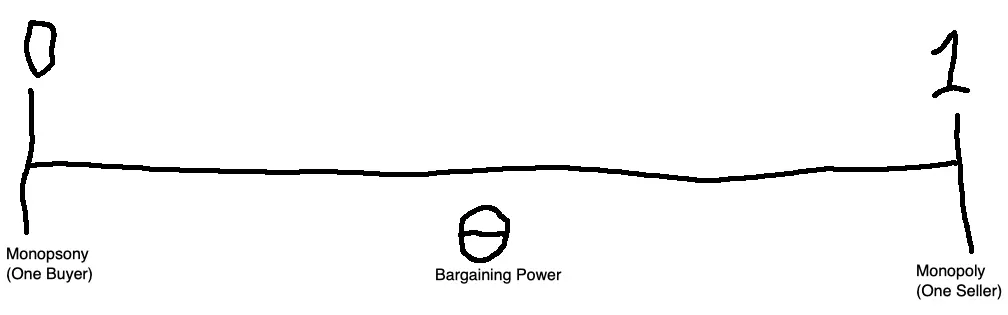

You can visualize bargaining power as a gradient from monopsony (one buyer) to monopoly (one seller):

For instance, in microeconomics 101 we’ll tell you that a worker’s wage (W) is equal to their marginal product of labor (MPL):

W = MPL

This equation makes no sense to anyone who’s ever worked - if I produce $250k worth of value for my employer, surely I’m paid less than that. A better model of wages would be this:

W = θ * MPL

Where θ is the bargaining power parameter between 0 and 1 we’ve seen above. Example where θ ~ 0 would be volunteer work, where the worker is so happy to do the work they do away with wages entirely.

You can find instances where θ ~ 1 in certain CEOs holding a stranglehold over a company. One example would be Adam Neumann, who cost $1.7B to fire as CEO. Another would be Elon Musk, who leads a postmodern pseudo-cult[footnote]It’s 2022, this is just the reality now[/footnote]. Which means Elon’s company, Tesla, can save on marketing costs and have a hilariously overvalued stock. But these only happen because of Elon specifically - he has θ = 1 against Tesla. Elon can capture all the economic value created from his cult of personality and put it in his pocket.

As a sidenote, low worker θ is currently a huge, society-wide problem. The term to look for is monopsony in the labor market [footnote]Remeber you sell your labor. So having few buyers means lack of worker bargaining power and suppressed wages[/footnote]. It’s the consensus from labor economics researchers that firms are maintaining monopsonies (either naturally or by cooperating to suppress worker wages) and lower worker bargaining power for profit[footnote]Also, a modern way to read Marxist takes on the labor market is just that θ is low and they’re unhappy about that.[/footnote].

Bargaining Power in a Home Sale

It’s easy to apply bargaining power analysis to a home sale. If there are few people selling their homes and many looking to buy, then θ is high (monopoly). In the reverse case, θ will be low (monopsony).

The concept of economic surplus now comes into play. A seller has a price where they’re indifferent between selling or not at this price. This is sometimes called a reserve price. Any price above that is a “surplus”, which makes the seller happy.

Same thing for a buyer - they have a maximum reserve price, and buying below that is surplus for the buyer.

If θ=1 there is only one seller, and a near infinity of potential buyers. In a bidding war, the buyer will often be told “you should bid something you won’t regret if you lose” which is human-speak for “bid your reserve price”. In this case, the sales price would be close to the highest buyer reserve price of the market. The buying market is “tapped out”.

Conversely, if there was one buyer and many sellers [footnote]I don’t know how that would happen, maybe you live in the Maldives in 2048 with water lapping at your feet. Or New Jersey right now, stuck with New Jersey all around you.[/footnote] then the sales price would be the lowest seller’s reservation price.

What does this have to do with agent fees?

In a “hot” market, where θ ~ 1, the richest buyer is already paying their maximum possible price. The real estate agent’s fees are built into that maximized price, so they can only be deducting from the seller’s economic surplus.

Conversely, in a market where θ ~ 0, the poorest seller is selling for their minimum possible price, so the real estate agent fees end up actually being paid by the buyer.

Takeaway: In very hot housing markets, the seller pays most the real estate agent’s economic cost. In cold markets, the buyer ends up paying more of the cost.

Why you shouldn’t hire an agent

Now we’ve established that in a hot housing market (like today), the seller is bearing the economic cost of the real estate agent.

It’s somehow a contentious issue that real estate agents are of any help to the seller hiring them. It shouldn’t be. In a market where sellers have the bargaining power, the seller outright loses heaps of money by hiring an agent.

There’s this famous freakonomics chapter making the claim that agents are incentivized to sell the house fast, rather than for a high price (here is the relevant text, p.5-8[footnote]It is the quintessential blend of commerce and camaraderie: you hire a real-estate agent to sell your home. She sizes up its charms, snaps some pictures, sets the price, writes a seductive ad, shows the house aggressively, negotiates the offers, and sets the deal through to its end. Sure, it’s a lot of work, but she’s getting a nice cut. On the sale of a $300,000 house, a typical 6 percent agent fee yields $18,000. Eighteen thousand dollars, you say to yourself: that’s a lot of money. But you also tell yourself that you could never have sold the house for $300,000 on your own. The agent knew how to —what’s the phrase she used?—“maximize the house’s value.” She got you top dollar, right? Right? A real-estate agent is a different breed of expert than a criminologist, but she is every bit the expert. That is, she knows her field far better than the layman on whose behalf she is acting. She is better informed about the house’s value, the state of the housing market, even the buyer’s frame of mind. You depend on her for this information. That, in fact, is why you hired an expert. As the world has grown more specialized, countless such experts have made themselves similarly indispensable. Doctors, lawyers, contractors, stockbrokers, auto mechanics, mortgage brokers, financial planners: they all enjoy a gigantic informational advantage. And they use that advantage to help you, the person who hired them, get exactly what you want for the best price. Right? It would be lovely to think so. But experts are human, and humans respond to incentives. How any given expert treats you, therefore, will depend on how that expert’s incentives are set up. Sometimes his incentives may work in your favor. For instance: a study of California auto mechanics found they often passed up a small repair bill by letting failing cars pass emissions inspections—the reason being that lenient mechanics are rewarded with repeat business. But in a different case, an expert’s incentives may work against you. In a medical study, it turned out that obstetricians in areas with declining birth rates are much more likely to perform cesarean-section deliveries than obstetricians in growing areas—suggesting that, when business is tough, doctors try to ring up more expensive procedures. It is one thing to muse about experts’ abusing their position and another to prove it. The best way to do so would be to measure how an expert treats you versus how he performs the same service for himself. Unfortunately a surgeon doesn’t operate on himself. Nor is his medical file a matter of public record; neither is an auto mechanic’s repair log for his own car. Real-estate sales, however, are a matter of public record. And real-estate agents often do sell their own homes. A recent set of data covering the sale of nearly 100,000 houses in suburban Chicago shows that more than 3,000 of those houses were owned by the agents themselves. Before plunging into the data, it helps to ask a question: what is the real-estate agent’s incentive when she is selling her own home? Simple: to make the best deal possible. Presumably this is also your incentive when you are selling your home. And so your incentive and the real-estate agent’s incentive would seem to be nicely aligned. Her commission, after all, is based on the sale price. But as incentives go, commissions are tricky. First of all, a 6 percent real-estate commission is typically split between the seller’s agent and the buyer’s. Each agent then kicks back roughly half of her take to the agency. Which means that only 1.5 percent of the purchase price goes directly into your agent’s pocket. So on the sale of your $300,000 house, her personal take of $18,000 of commission os $4,500. Still not bad, you say. But what if the house was actually worth more than $300,000? What if, with a little more effort and patience and a few more newspaper ads, she could have sold it for $310,000? After the commission, that puts an additional $9,400 while she earns only $150, maybe your incentives aren’t aligned after all. (Especially when she’s the one paying for the ads and doing all the work.) Is the agent willing to put out all the extra time, money, and energy for just $150? There’s only one way to find out: measure the difference between the sales data for houses that belong to real-estate agents themselves and the houses they sold on behalf of clients. Using the data from the sales of those 100,000 Chicago homes, and controlling for any number of variables—location, age and quality of the house, aesthetics, whether or not the property was an investment, and so on—it turns out that a real-estate agent keeps her own home on the market an average of ten days longer and sells it for an extra 3-plus percent, or $10,000 on a $300,000 house. When she sells her own house, an agent holds out for the best offer; when she sells yours, she encourages you to take the first decent offer that comes along. Like a stockbroker churning commissions, she wants to make deals and make them fast. Why not? Her share of a better offer—$150—is too puny an incentive to encourage her to do otherwise.[/footnote]). We don’t need to speculate on the effect: there are studies on the matter and they show the seller clearly losing value. Losing 6% of your house’s sale price is a lot of money! For most people this is the equivalent of months of work.

Let the auction do the work for you

Despite the data showing that agents don’t help the seller get a better price, you may argue that perhaps arranging the final sales price is a difficult job. A job so complex that only a veteran real estate agent can do it for you.

Nonsense.

In a hot market, the price is simply set by a first price auction. In the current housing market in Montreal, it’s common to for agents show a house for a week, and ask for all offers to be made blindly by a specific date.

There isn’t much to do here! The first price auction will lead to buyers bidding up to their comfort level given the amount of competition they expect to run into in the bidding war. You simply don’t need an agent to ask for people to submit a bid by a certain date.

Real Estate Agent Fee Bargaining Power

Real estate agents are harmful to their clientele. Moreover, showing houses and making sure buyers and sellers are signing the correct pre-prepared paperwork isn’t rocket surgery.

In a perfect world, competition would enter to ensure that real estate agents’ bargaining power against home buyers and sellers get close to θ ~ 0. They shouldn’t be able to suck much money out of the economy and buy their Mercedes with.

But clearly agents are buying overpriced German sedans. Then, why isn’t the agent’s cut driven to zero?

…

Because real estate agents are unionized![footnote]and also sellers are dumb, as we’ll see in the next section[/footnote]

Unions are a great way to increase your θ. They create a pseudo-monopoly where there normally wouldn’t be one by aggregating many economic agents into a single one.

In my province (Quebec), agents literally have a union. It of course does occupational licensing, the thing all good economists hate. They also somehow managed to win a court case letting agents have exclusive access to sales price data, permanently harming housing market researchers. Look at them being mad at self-listing services

ppl r dumb lol

Its clear than in a hot market, sellers should not be hiring an agent. If you hate money so much, please just give it to charity instead.

Even worse, it seems that sellers somehow pay agents at a price point of θ > 1[footnote]Since agents lose money to their client, their wage is above their marginal product of labor. This means θ > 1[/footnote]!!

This is crazy. It shows why predicting economic behavior is difficult – people are very very dumb.

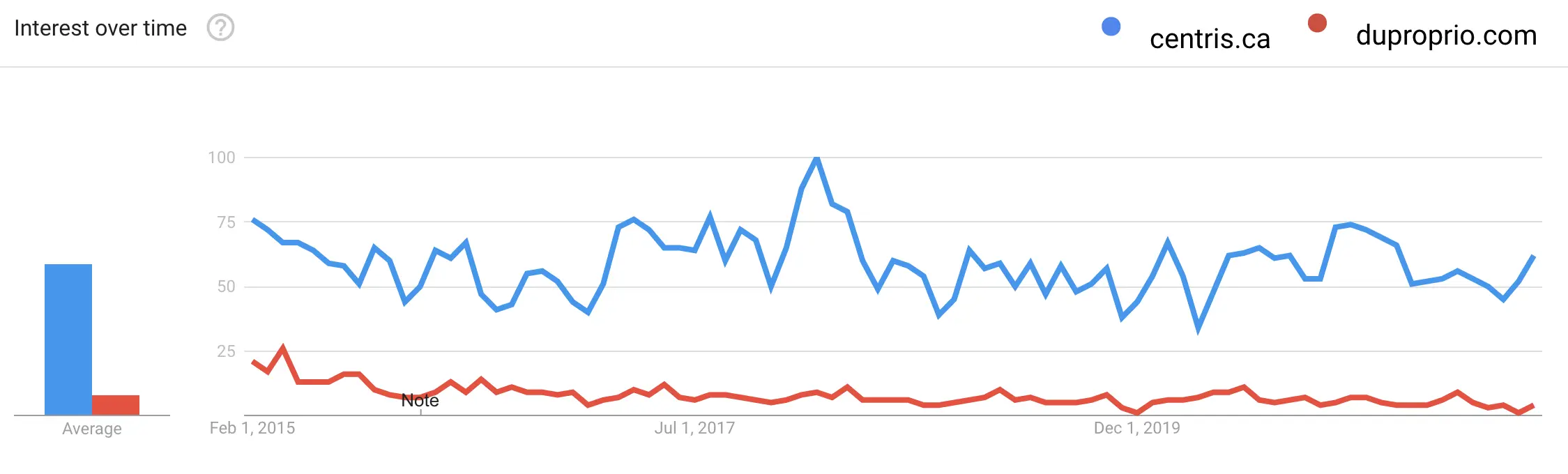

I couldn’t easily access to self-listing versus agent-listed data, but in Quebec the two are easily segregated into two websites: centris.ca (agent) and duproprio.com (self-listing). An agent told me around 97% of homes were sold through agents. This checks out with google trends data on the two listing platforms:

What’s impressive here is that self-listing popularity did not increase as the Canadian housing market went through its hottest period in history! Home sellers are completely inelastic in their listing strategy to the market conditions, even if it costs them very large sums of money.